Wíyukčaŋ means consciousness or all–knowing in the Lakota language of the Sioux tribes.

Since colonialism and the ensuing rise of capitalism, western society has undermined and cast aside this Indigenous wisdom. Now, as we grapple with the devastating effects of extractive systems in the West, we’re realizing we should have listened to the greatest protectors of our earth a long time ago.

The question is, are we too late?

There are an estimated 476 million Indigenous peoples worldwide. Though they comprise only around 6 percent of the global population, they protect 80 percent of biodiversity left in the world. In the U.S., they’ve lost an alarming 99 percent of their land to European settlers, removal policies, and forced migration. These colonial policies continue to affect tribes today, many of which have been relocated to less valuable lands where they’re excluded from participating in energy, forestry, and natural resource industries and are more vulnerable to the climate crisis (e.g. poor air quality, extreme weather and heat waves, and flooding).

Where the narrative goes wrong today

What’s concerning to me is that many of the privileged counter-culture conversations about the climate crisis today center on building doomsday bunkers and learning survival skills. Or worse, co-opting the growing and land management techniques used by Indigenous peoples for centuries, for personal gain. There’s nothing inherently wrong with building these capacities, especially if it helps in a crisis. But this individualist narrative perpetuates the same attitude that gave rise to colonialism and misses the larger point—that if we truly listened to Indigenous wisdom, we would stop the climate crisis together, not buy another survival knife.

So how can we be better stewards of Indigenous wisdom? There are plenty of articles about what we can learn from them. This post is more about reorienting ourselves within our culture and, in turn, making strides to reorient that culture toward their wisdom. Today is International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, this cultural change should be part of every day.

Where understanding begins…

Here are a few ways to incorporate Indigenous wisdom into your life and community.

Look deeper into lessons from Indigenous language

Indigenous languages emphasize verbs. They are alive. Western languages are noun heavy. They ‘thingify’ words to organize, harmonize, and ultimately, dominate. Where our language says a tree as a thing, Indigenous language might say ‘treeing,’ expressing its aliveness, complexity, and nuance. Another example is in Indigenous peoples’ fluid naming conventions. Names, drawn from nature, can be changed to express personality, progression, or life circumstances. Furthermore, Indigenous naming conventions were non-binary well before the Western world began enforcing monolithic gender norms. Only now are we starting to have conversations about the impact of these problematic gender conventions in the West.

With 40 percent of the 7,000 Indigenous languages still spoken in danger of disappearing, we must support their preservation to ensure Indigenous peoples’ identities aren’t further erased by the dominant society. If you’re passionate about this, you can support numerous grants that fund language preservation. If you’re in Canada, you can donate to the First Nation’s Native Language Immersion Initiative. You could also learn how western culture is institutionalized through biases in knowledge organizational systems like the Dewey Decimal System, which underrepresents Indigenous voices in libraries across the nation. Systems like the Brian Deer Classification System at the University of British Columbia are designed for flexibility to reflect local Indigenous communities, but more systems like this are needed.

Share reverence for Indigenous land and farming practices

Crop rotation, intercropping, and polyculture practices, which enrich the soil and lead to more sustainable yields, largely originated in Indigenous communities. While these farming practices run counter to the dominant monoculture agriculture systems in America today, they are giving rise to more sustainable practices like regenerative farming and permaculture. What’s more, they can be utilized by small and large-scale farmers alike. Acknowledging the origins of these traditional growing practices is a step forward. You can read more about Indigenous contributions to sustainable agriculture here.

Take inspiration from Indigenous collective action

Despite losing land and sovereignty, Indigenous communities continue to rally for environmental justice and stand at the frontlines of the climate fight. Look at how they led successful protests against the Keystone XL pipeline and drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. In fact, a report by Indigenous Environmental Network and Oil Change International found that Indigenous-led resistance to 21 fossil fuel projects in the U.S. and Canada over the past decade prevented at least 25 percent of annual emissions.

Indigenous peoples go beyond just stewarding the land, they actively protect it for everyone. Let’s find inspiration in their collective power and seek ways to stand by them in the fight against extractive systems. With these points in mind, we can observe and question the world around us with more depth. I encourage you to look for and work to dismantle colonial ideals in your everyday life. Talk about what you learn with your community and on social media. Be an ally and stop Indigenous erasure. Honor the land you live on by giving a name to it. Shop and support Indigenous businesses.

To help you do so, and because this is predominantly an apparel blog, I’ve curated this list of leading Indigenous designers you can follow and support today as one part of a larger cultural shift.

EMME Studio

This line reflects its founder, Korina Emmerich’s approach to social and climate justice. Korina is originally from the Pacific Northwest and her colorful work reflects her Indigenous heritage from The Coast Salish Territory, Puyallup tribe. She makes her clothes and accessories by hand from upcycled, recycled, and natural materials in her Brooklyn studio located on occupied Lenapehoking land. If you’re looking for a set fit for fall, check out the peridotite jacket and cropped pant.

Orlando Dugi

Making his garments made by hand, weaving with wool or sewing with cotton or silk, and using traditional dyeing and ornamentation techniques are ways Orlando continues his rich Navajo culture. He uses beading and detailing in his custom designs to reflect the flora of his land and astronomical knowledge passed down through generations. Learn more about Orlando’s process in this video.

Robin Waynee

Award-winning fine arts jeweler Robin Waynee is renowned for her intricate metal work and brilliantly set precious stones. She is a member of the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe and was born and raised in Mio, Michigan. Robin is the only jewelry designer who’s received the Saul Bell Jewelry Design Award three times in a row.

Jamie Okuma

This multi-disciplinary artist’s couture and ready-to-wear designs have been featured in galleries, exhibitions, and publications across the nation. Jamie is Luiseno, Shoshone-Bannock, Wailaki, and Okinawan and is also an enrolled member of the La Jolla band of Indians in Southern California where she lives and works.

Liandra Swim

This Aboriginal-owned and operated Aussie brand highlights the achievements of indigenous women with limited edition, reversible swim styles made from recycled materials. Check out the brand’s vibrant Deep Sea Collection where each piece is named after a pioneering Aboriginal woman.

Ahlazua-Indigenous Woman Made

This metal work studio reflects the designer’s given Euchee/Yuchi name ‘Ahlazua’ and honors their Choctaw, Euchee-Mvskoke Creek, and Diné tribal heritage with traditional techniques using shells, pearls, and turquoise, as well as unique cutting and carving techniques. I love this stackable coral and seed pearl ring.

Patricia Michaels

A Project Runway runner-up, Patricia has been a pioneer of sustainable fashion that honors her native roots for over 20 years. She designs her collection, PM Waterlily (after her Native name), in Santa Fe, New Mexico, working with organic materials and hand-dyeing and painting her fabrics, often using algae pigments. She showcases nature’s influence by using fluid textures to create movement and imbue individuality.

Poyomishukwin Swimwear

This modern collection of cutout swimwear is handmade and designed on Yadanchi Yokuts land with all women in mind and Indigenous women at heart. Many pieces are designed with remnant materials from past collections, reducing cast-off waste.

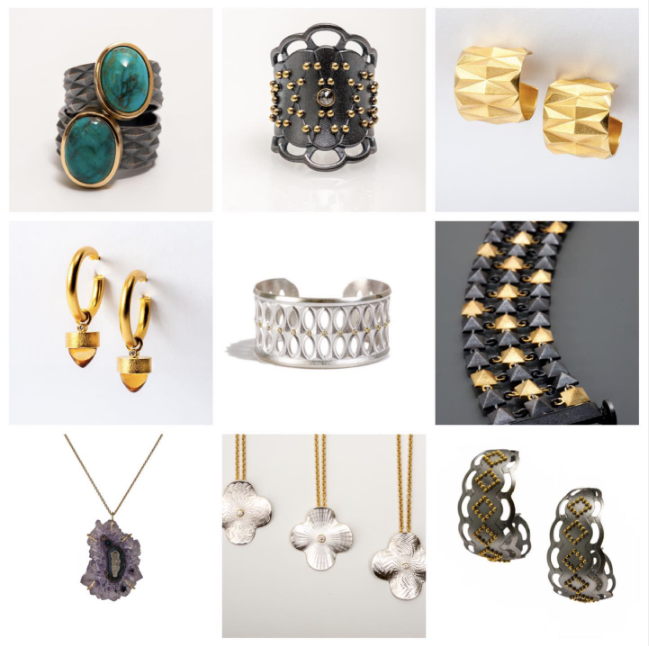

Maria Samora

Master metalworker, Maria Samora’s jewelry is inspired by Pueblo tradition melded with modernity. Her designs are simple, elegant, and embody the natural movement and life of the wearer. She works with ethically produced 18k gold and sterling silver in her Taos, New Mexico studio.

It should also be noted that while he has passed, Cherokee designer Lloyd Kiva New paved the way for many of these designers and others that will follow. In 1951, he became the first Native American to show at an international fashion show. At a time when Native cultures were being erased or melded into American cities through relocation and termination policies, upper-class Anglo women were wearing his garments, giving him a rare and important platform to represent the contribution of Natives to American society. He frequently did this by collaborating with other Native designers as well.

__

This post focuses mostly on the prominent figures in Indigenous design (mostly Native American) and is not meant to be exhaustive or reflective of the global contribution of Indigenous peoples to apparel or textile design. I hope that it inspires you to explore the world of Indigenous design deeper on your own. Indigenous Fashion Arts is a good platform to discover more. If you follow an Indigenous designer or want to share specific knowledge I haven’t covered in this piece, I encourage you to do so in the comments.

If you want to learn how to protect Indigenous Land, read this post.